-

Opere

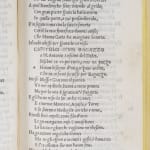

Terze rime del Molza, del Varchi, del Dolce e d'altri. (Venezia) per Curtio Navò et Fratelli, 1539

In 8°, 80 cc.nn. Legatura del secolo XIX in mezzo marocchino con ricchi fregi dorati al dorso. Ottimo esemplare€ 9,000.00Further images

La cultura letteraria fiorentina inizia ad aprirsi, forse per la prima volta, alla poesia omoerotica tra la fine del Quattrocento e i primi decenni del secolo successivo. Prima il Burchiello,...La cultura letteraria fiorentina inizia ad aprirsi, forse per la prima volta, alla poesia omoerotica tra la fine del Quattrocento e i primi decenni del secolo successivo. Prima il Burchiello, poi il Berni e i poeti che lo circondavano, cominciarono a comporre e poi, più tardi, a dare alle stampe poesie che, attraverso l'uso di doppi sensi e parole chiave, di solito con termini legati al cibo e di uso comune (cardi, anguille, pesche, aghi, ecc.), avevano espliciti riferimenti a relazioni omosessuali e all'erotismo gay.

Questo libro appartiene al genere della "poesia bernesca" (dall'autore Berni). Si tratta della vera prima edizione, quella originale, che fu ristampata l'anno successivo per diventare il secondo volume delle opere di Berni, sempre edito da Navò. Gli argomenti sono i più vari, tutti più o meno erotici o di natura godereccia. Si va dalle insalate alle osterie, dalle uova sode alla ricotta, dai finocchi alle serrature e alle chiavi. Ma quest'opera contiene anche una lunga composizione piuttosto esplicita di Ludovico Dolce, intitolata "Capitolo di un ragazzo". Tra la fine del Quattrocento e i primi decenni del Cinquecento fiorì a Firenze una cultura letteraria che forse per la prima volta si apre ad una poetica omoerotica. Prima col Burchiello e poi col Berni e i poeti che lo circondavano, si cominciano a comporre e poi astampare poesie che, con l'utilizzo di doppi sensi e parole a chiave, utilizzando vocaboli di generi commestibili o d’uso (cardi, anguille, pesche, aghi, ecc.), avevano riferimenti espliciti ai rapporti omosessuali.

“(1497–1536), Italian author. Born in the Florentine hinterland, Berni studied in Florence and developed a love of playful, populist poetry in the tradition of Burchiello. In 1517 he moved to Rome and entered the service of his distant relative, the cardinal and literary figure Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena (1470–1520), after whose death he worked for his nephew, the Apostolic Proto-Notary Agnolo Dovizi da Bibbiena. In 1523, Bibbiena exiled Berni to the abbey of San Giovanni in Venere, in Abruzzo, to punish him for a homosexual scandal about which little is known. Since the scandal had cost him his job, when Berni returned he entered the service of the austere reformist bishop Giovan Matteo Giberti (1495–1543), with whom he went to Verona in 1527. Five years later, tired of Giberti’s rigour, Berni found employment with Cardinal Ippolito de‘Medici, whom he followed to Bologna, Florence and Rome. In 1534, he returned to Florence and engaged with the Medici court. Such frequentations proved fatal, as he was drawn into intrigues and the struggle between Ippolito and Alessandro de’ Medici for control of the Florentine government: Berni was himself poisoned when he refused to poison Ippolito’s supporter, Cardinal Giovanni Salviati.

Berni’s fame rests on his comic com positions (called ‘chapters’), which are written in two registers. On the surface, the poems offer either praise to objects of trifling importance (a needle, fennel, fish) or disdain (the plague). The words, however, are always used with a double meaning which is sexual and very often homosexual. This type of poetry enjoyed a great success and was called ‘Bernesque poetry’ after the writer; among other practitioners were

Angelo Firenzuola (1493–1543), Andrea Lori (sixteenth century), Matteo Franzesi (sixteenth century) and Giovanni Della Casa (1503–1556), who was rumoured to have written a book titled De laudibus sodomiae seu pederastiae (‘In praise of sodomy, that is to say, pederasty’), a volume which in fact never existed. These poems were collected in three volumes. Several of Berni’s followers as well showed a preference for homosexual themes, such as Benedetto Varchi (1503–1565), Lodovico Dolce (1508–1568), Francesco Maria Molza (1484–1544) and Anton Grazzini (‘Il Lasca’) (1503–1584).

The most shocking aspect of Berni’s poetry is that not only did he celebrate sexuality in all of its forms (including homosexuality), but he breached the machismo rule of the Renaissance (according to which sodomy could only be written about in the voice of the ‘active’ partner). Berni’s poetry, in contrast, also exalts passive sodomy. For instance, in a 1533 poem in which he discusses the danger of being captured by Turkish pirates while travelling by sea, Berni declares: ‘I already warned several officers/and prelate friends of mine: “Be careful/because in these countries prisoners are impaled”./ And they replied: “We are not frightened;/ if this is the only harm we shall receive /we shall consider it an advantage and a piece of good luck;/furthermore for such a pleasure/we shall intentionally go as far as to Trebizond/so that what has to be done be done as soon as possible”./While I was writing this, I was reminded/about our dear Molza, who once told me/about them in a very solemn way:/somebody once told me: “Molza, I am that crazy/ that I would like to become a vineyard/to have plenty of stakes and change them as frequently as possible”./…/Molza replied: “Therefore haste to put our hand on oars/…/let’s sail, since I would also like /to be that gloriously impaled”’.

Berni went so far as to use his coded language to ask a friend of his for ‘hams’ (i.e. both ‘buttocks’ and ‘catamites’) in private letters of 1550–1551. (The friend, Vincilao Boiano [1485/1490?-1560], who as a young man had also written love poems to Giovan Matteo Giberti, seems to have been particularly skilled in spotting young men who were available for sex.) Berni even praised as an ‘utterly lucky man above any other man he who/can both give and take “peaches” [i.e. “pricks”]’.

His Latin poetry, in which he no longer needed to resort to doubles entrendres to write about his love for a youth, is particularly explicit. These verses, which were written in a moment of desperation, when Berni’s beloved was stricken with plague and seemed to be on his deathbed, are among his most sincere and delicate works. The unexpected recovery of the youth provided the occasion for a Latin poem in which Berni gave vent to his joy. Berni is, in sum, one of the most interesting poets of the Italian Renaissance, not only for what he wrote, but also for his network of friends, which included several outspoken homosexually inclined men.

Carmina quinque illustrium poetarum, Florence, 1562:137–59, 164–5); F. Berni, Rime burlesche, Milan, 1991; G. Dall’Orto, ‘Bernesque Poetry’ and ‘Burchiellesque Poetry’, in W. Dynes (ed.) Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, New York, 1990:131–2, 173–4; G. Dall’Orto, ‘Chiamiamoli prosciutti’, Babilonia, 123 (June 1994): 71–3; J. Wilhelm (ed.) Gay and Lesbian Poetry: An Anthology from Sappho to Michelangelo, London, 1995: 311–13.

(Giovanni Dall'Orto, Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II, pp. 62-63)

"In 1515, Berni left Florence for Rome, where he made his living as secretary to various men of the cloth. Rome was much suited to his gay, humorous character, and he became the darling of literati and artists at the papal court. During this period Berni became a member of the Roman Accademia dei Vignaiuoli. This institution was typical of the festive social and literary organizations that flourished in Italy in the sixteenth century. Its members included famous contemporary burlesque poets such as Mauro, Della Casa, Firenzuola, Bini, and Molza. Together they established a convivial and facetious atmosphere, reciting their outrageous verses for the pleasure of priests and literati alike. The Vignaiuoli adopted the names of plants and herbs in keeping with the name of their academy, as was the custom. Thus they were il Mosto, l'Agresto, il Fico, il Cardo, il Radicchio, and similar." (Francesco Berni and the Burlesque Sonnet in the Sixteenth Century)

Non presente in Gamba e nelle altre bibliografie pertinenti; EDIT16 CNCE 59490: solo tre copie di questa prima edizione sono registrate in collezioni pubbliche italiane; una copia è registrata fuori dall'Italia a Ginevra.

8di 20

Iscriviti alla newsletter di Orsini arte e libri

* campi obbligatori

Tratteremo i dati personali che hai fornito in conformità con la nostra informativa sulla privacy (che trovi linkata nel footer). Puoi annullare l'iscrizione o modificare le tue preferenze in qualsiasi momento cliccando sul link presente nelle nostre email.